New York Post

September 11, 2010

Rufus “The Stunt Bum” Hannah had smashed his head through a plate-glass window, but for the teens egging him on, it wasn’t enough. Ryan McPherson, the cameraman, kept taunting the 45-year-old homeless man. Was he “down” or what? Hannah and his best friend Donnie Brennan, a 55-year-old Vietnam vet, wobbled around each other drunkenly. It was another sunny day in the middle-class enclave of La Mesa, Calif. Another day lost to alcohol and the vulgar entertainment of bored teens. Was Hannah down? Yes, he thought, and sucker punched Brennan in the head.

Brennan collapsed with a broken ankle. Hannah kicked his friend as the wounded man pleaded for someone to call 911. Eventually, the ambulance arrived and Brennan was carried out on a stretcher.

“But they still kept filming,” The Stunt Bum says of that February 2001 afternoon. “What I did bothers me every day.”

Any list of the worst examples of human nature, of the reprehensible dark side of suburbia, must include “Bumfights.” A series of underground videotapes produced in the early aughts, they featured homeless men fighting each other and performing agonizing stunts. They did this for beer or vodka provided by 17-year-old McPherson and his friends. Despite the public outcry, and eventual legal battle, McPherson made about $6 million from his voyeurism, and continues to produce controversial videos.

The Stunt Bum barely walked away with his life.

“I was a human piñata,” Rufus Hannah says in his new memoir.

Eight years sober, Hannah explains how a lifelong addiction to alcohol brought him to becoming an unwitting gladiator for twisted teens. “It was controlling me with every move I made,” he says in a polite Southern drawl. “I was at a weak point in my life.”

Hannah grew up in the backwoods of Georgia, hanging out from the age of 10 with a “couple of older gentlemen who were drinking every day at the mini-mart gas station.” By age 19, his devil-may-care ways had left him a dropout, married to his sweetheart Gail, raising two kids on a construction worker salary.

“It seemed like I went from a teenager overnight to being a husband and father,” he says. “I couldn’t handle it.”

Instead, he joined the army. Though his courage would have made him a “fine soldier,” the guys in his platoon had been teasing him about his out-of-shape body, Hannah says. He ruined his chances with a cheap plea for their attention — a pattern that would repeat itself often in his life.

As he tells it, a long, hard rain had fallen on Fort Leonard Wood, Mo., turning the obstacle course into “a swamp.” “I climbed up the ladder and down it, had a little trouble with it because I’m a short person,” he says. “On the last step, that’s when they began cheering me. That felt good. So I raised my arms to cheer with them and I slipped and fell and broke my elbow.”

Eight months and several surgeries later, he was medically discharged in 1982.

He has only a vague memory of the “lost” years that followed, recalling “farming” for a while in a small, unnamed town somewhere in the south before arriving in California. Hannah landed on the coast in 1991 — drifting into the growing population of homeless vets centered in La Jolla.

One bright spot in a “real lonely” big city existence was Donnie Brennan, a wizened, longhaired vet — with two battle-related injuries and a PTSD diagnosis — who could be found in the smoking lounge telling “folk stories” about Vietnam. Brennan would kid Hannah about his abortive one-month service stint and regale him with tales of his comfortable 1950s middle-class upbringing amongst “new Chevys and Schwinn bikes” in nearby La Mesa. Buoyed by the promise of being the only two homeless men in a relatively small and safe suburb, the pair soon boarded a bus for La Mesa.

Donnie’s mother’s household provided the two alcoholics with a measure of stability for a while. “We were showering frequently and had clean laundry,” Hannah says. But soon, a swelling tide of homelessness in the area “increased competition” for already scant resources — and they were as broke as before.

By 2000, the pals had been living behind Vons’ grocery store for nearly a decade. When Hannah wasn’t dumpster diving and rolling his battered supermarket cart through the back streets of La Mesa, he would lie on the concrete pavement gazing up at the stars, thinking about Gail and their two kids.

That’s when Donnie first befriended Ryan McPherson, a senior at Donnie’s local alma mater, Grossmont High. With his arms covered in tattoos, and his long messy hair, McPherson cut a strange figure at the local park, silently filming members of the town’s growing homeless population.

The first night that Ryan told Donnie he was going to meet them behind the Vons, Hannah was especially vulnerable. It had been nearly 24 hours since he’d had his last drink, and withdrawal was setting in. The DTs would start soon and then there would be nothing he could do except shake and hallucinate. “You sure he’s coming?” Hannah asked before passing out. He awoke to the sound of an SUV pulling up and Ryan was standing over him with a cocky grin. Hannah remembers seeing another guy in the front seat and two giggling girls in the back. “They were gawking at me like they were at the zoo,” he says.

Asked if he was interested in performing for a movie, Rufus muttered that he just needed a drink. The underage but always resourceful McPherson managed to score a six-pack and the pair wolfed down three beers apiece. For his first “scene,” Rufus climbed into a shopping cart and was pushed down a flight of concrete steps by one of McPherson’s crew. His body “slammed into the pavement.” He couldn’t scream because he was gasping for air. Sliced open, his pinkie gushed blood. He “knew I could have broken my neck,” but when he was handed an open beer, he didn’t hesitate. McPherson had found his man.

The “Bum Fights Krew” — which included Rufus, Donnie, McPherson and Daniel Tanner, a “filmmaker” from Las Vegas — were soon making “preliminary tapes” and selling them at local bars and high schools.

As the “stunts” became more arduous, Hannah needed increasing amounts of alcohol to ease the physical pain and blunt his mounting terror of being paralyzed or killed.

“A lot of times they would bring a cheering section with them,” Hannah says. “Ryan would call the stunts. And then I would hear them cheering me, ‘Yeah, you’re the man. You’re the man.’ I guess it made me feel important.”

While he “liked to see blood,” according to Hannah, McPherson knew how to feign compassion to get a scene he wanted. One Thanksgiving night, he came by Vons with a Tupperware of turkey and a few bottles of wine. After convincing Rufus to call his sister using his cell, Ryan turned on his camera and waited for pay dirt. Rufus soon heard that Gail had told their kids that he was dead. “That was the most pain I had felt in a long time,” he says. “I didn’t know if I could handle it.”

Ryan was still laughing and filming so Hannah made a split-second decision to “handle it” the only way he knew how. Climbing up onto a ledge, he jumped two stories onto the concrete below.

“I felt like someone had snapped my spine in half,” Hannah says, adding that the physical pain dulled the sense of loss he felt about his kids. Ryan handed him a bottle of vodka and he took it.

One night that same winter, McPherson and a friend found the two — who were drunker than usual — wobbling in the parking lot of a Taco Bell. They offered Donnie money to “do a dare” but he turned them down. “You friggin’ chicken,” Ryan persisted. “I need you to get a tattoo. Just like in Vietnam.”

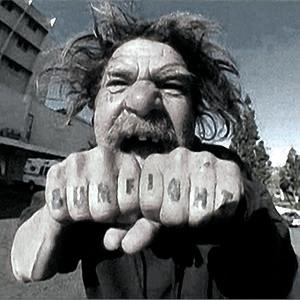

Donnie gave in and got in Ryan’s car alone, and they drove to Inkers, a tattoo parlor in San Diego. The next morning, he woke up inside a tattoo parlor with a bandaged head. He peeled the bandages off to reveal “BUMFIGHTS” in stark black lettering across his forehead. Hannah would later get a similar tattoo on his knuckles.

“I have no doubt they were trying to brand us for life,” Hannah says. “I think they had something even more sinister in mind for us.”

By summer of 2002, the La Mesa district attorney’s office — in the course of an investigation of Ryan McPherson — had contacted local businessman Barry Soper, who previously had given Donnie and Rufus some odd jobs. Hearing what his ex-employees were involved in, Soper began looking for two, but they had been spirited away to Las Vegas, where they were being kept in a “safe house.” After McPherson was arrested early in August of that year, Soper received a phone call from Donnie. Within hours Soper had “rescued” the two and reporters had set in with a blizzard of questions about the case.

Despite what Soper calls a “strong case,” McPherson and his co-defendants wound up with a slap on the wrist: community service. Adding insult to injury, they skipped their sentence by forging documents claiming they had already performed the service. When discovered, they were ordered to serve six months at what Hannah calls a “summer camp.” It was the same facility where he himself was once housed after being busted on a string of vagrancy charges.

McPherson was unrepentant. “We’re merely exposing something that I don’t think a lot of people know exists,” he said in an interview at the time. “I think it’s interesting. I can’t imagine what would make somebody do the things that Rufus was doing to himself.”

Hannah’s stunt career has exacted a harsh toll. He has double vision, poor equilibrium, and has suffered through innumerable operations to remove the “BUMFIGHT” tattoo on his knuckles with little success. But the memory of the pummeling he gave his best friend is probably the most painful scar from that time.

Donnie hasn’t been so lucky. He spends his days drunk and alone, living off disability and a “Bumfights” civil settlement that reportedly was less than $100,000 for each of the men. His forehead is still tattooed. “Moving on from Donnie,” Hannah says softly, “broke my heart.”

Through all his hardships, Hannah somehow retained a sense of self, which eventually allowed him to quit booze, go back to school and work full-time. “No matter how low you get,” he says, “you can better yourself.” He now manages the same La Mesa apartment complex where Soper found him dumpster diving so many years ago, and he advocates for homeless vets through Stand Down, a non-profit advocacy group.

McPherson hasn’t changed, claiming in 2006 that the videos did Hannah more good than harm. “In a way [the videos] saved his life,” he said.

Other members of the “Bumfights” cheering section, now young adults, sometimes see Hannah on the street. “ ‘Good seeing you, buddy. I’m glad you’re doing good,’ ” they’ll say. “’You’re looking good, man.’ ”

“That’s how people know me, as the ‘Stunt Bum,’ ” Hannah says. “Sometimes it breaks me down a little bit.”

A Bum Deal

An Unlikely Journey from Hopeless to Humanitarian

by Rufus Hannah and Barry Soper