Animal

September 27, 2012

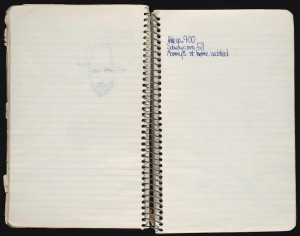

If you want a well-guarded, white-gloved peek at what’s billed as Jean-Michel Basquiat’s earliest known work, the “SAMO© high-school notebook,” you can find it in Yale University’s Beinecke Library, a gleaming modernist temple to rare books and manuscripts, which holds, among other priceless treasures, two volumes of an original Gutenberg bible. Gently flip through the slightly yellowed pages of the now tattered and coverless 6”x9” spiral notebook and you’re light-years away from the picture-perfect Ivy League campus.

But this time capsule is central to a new legal case that challenges an important part of Basquiat’s legacy. To understand the roots of the dispute you need to go back to the graffitied and grime-specked late 1970s, when Basquiat was in his last year at Manhattan’s City-As-School. One night in ’79, the 19-year old Basquiat and his teenage pal Al Diaz “were tripping in that little park near 14th Street and 7th Ave,” recalls Diaz, puffing a Marlboro in a blacked-out bar under construction on E. 6th Street. That’s when Basquiat uttered a psychedelic-inspired prediction that has been seared in Diaz’s memory ever since: “Jean tells me, ‘Al, I think I know I’m going to be famous and I think I’m going to die young.”

Today, Diaz, a struggling visual artist, is working as a carpenter on the rock-n-roll-themed bar with Shannon Dawson. Dawson introduced Diaz to Basquiat when the three were students at City-As-School—a high school for “fuck ups,” Diaz clarifies. Dawson, who was one of the founding members of Basquiat’s noise-rock project Gray and later had a briefly successful career as a funk musician, pipes in: “Jean’s three heroes were Jim Morrison, fucking Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison.” Still ruminating on that night in the park, Diaz adds: “And Jean-Michel died at 27. It was kind of a prophetic statement.”

By now the story of the late painter’s rocket-rise to fame is the stuff of media legend — first laid down by critic Renee Ricard’s 1981 Artforum piece, “Radiant Child,” and then nailed into public consciousness by fellow 1980s art-star Julian Schnabel in his indie-film hit “Basquiat.” The legend tells of a street urchin who ran away from a middle-class Brooklyn home and dazzled the downtown art scene with his witty “SAMO” tags spray-painted on walls all over lower Manhattan before going on to high–art superstardom with his neo-expressionistic canvases. In this tale, the SAMO© tags plays a seminal role.

But now, a complex legal battle involving Dawson, Diaz and Yale University’s purchase and appraisal of the “SAMO© notebook,” (which supposedly contains some important early writings by Basquiat) puts part of that tale in doubt. At its core, a lawsuit, reportedly launched by Dawson and Diaz in May of 2012, alleges that the august Beinecke is passing off their high school scribblings as priceless Basquiat juvenilia, and that the book is stolen property to boot. (In its catalog entry, Beinecke does not dispute that the book was originally Dawson’s property and contains his writings.)

The tag SAMO© was an acronym that actually came together over time, Diaz explains: “Its hard to actually say who came up with it because everyone our whole crew—Shannon included—used that word it was like it meant Same ol’ shit right?”

According to Diaz and Dawson, Diaz’s contribution to SAMO© was much greater than he has been given credit for. Diaz, who along with Dawson is white, says, “I introduced [Basquiat] to graffiti, he wasn’t a homeboy that was going to come up with a nickname, we all hit on the idea of SAMO as a study in hype, but then he kind of took it ran with it.” Citing another recent legal entanglement, between the estate of Keith Haring and a graffiti artist named LA II, critic Hrag Vartanian says that questions about provenance are bound to arise when it comes to street art: “Perhaps the idea of sole authorship is an outdated modernist concept.”

Outdated or not, this concept is central to traditional journalistic narratives about “outsider” artists. And, even more to the point, it is essential to the buying and selling of art as a commodity with a “name brand” attached. Certainly, no brand name was more important during the go-go art market of the 1980s—which of course paralleled that era’s swinging stock market—than that of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Speaking of the notebook, Dawson says with growing annoyance, “I never even knew it had left my apartment until [former Basquiat assistant] Stephen Torton called me and told me it was in the Beinecke.”

While neither Yale University or John Pelosi, Diaz and Dawson’s attorney, will talk about the case, certain facts seem indisputable. In 2009 an agent working for rare book seller Glenn Horowitz in Chelsea bought the notebook from a woman formerly involved closely with Dawson (ANIMAL has promised Dawson not to divulge her name) for a sum widely believed to be between $25,000 to $40,000. She had apparently sold the book under the pretenses that Dawson was dead, and therefore it was her property. Subsequently the Sinclair fund, a higher-education devoted philanthropy, purchased the book for the Beinecke for a much higher sum. Reached by phone, Horowitz was not forthcoming. He knew the book, thought it was “an important” find, but couldn’t help any further because the agent who sealed the deal was “no longer with the company.” I seemed to be the first one to apprise him of the lawsuit. He said: “I’m not at all worried about it, I’ve never even heard of it! I handle phone calls like this every day, I deal in cultural ephemera.” Asked if he shouldn’t have at least done a little digging to figure out if Dawson was, as the original seller had claimed, really dead, he replied, “That line of argument is beyond juvenile.”

The allegations of impropriety raise serious questions not only about the Basquiat legend but also about the Beinecke’s reputation as perhaps the pre-eminent repository of rare books in the world. Hrag Vartanian maintains that normal protocol was not followed if Yale went completely on “Glenn Horowitz’s word” to authenticate the notebook’s provenance. He adds: “This isn’t like some small time buyer. It’s a major institution and if they didn’t research it, it’s a big deal.”

As far as Dawson is concerned, neither Horowitz nor Yale did any research at all. “No one even thought to even do a Facebook search to see if I was still alive,” he says.

On one of the two occasions I personally checked out the spiral notebook, the Beinicke librarian said with a sigh, “We’re not going to be able to let this one out soon, its just too valuable and fragile.” Yale employee and sometime professor Louise Bernard informed Dawson and Diaz that she had taught several classes around the book, they claim. A Google search brings up multiple instances of art scholars’ soaring rhetoric about the importance of the spiral notebook to Basquiat’s later ouevre. One such monograph uses passages from the beaten-up artifact to confirm the artist’s early “preoccupation with authority, artistic, literary and musical.” Yet Dawson claims that the text in question was written by him, not Basquiat. (Diaz estimates there are three passages by Basquiat in the book—”and none of the SAMOs.” Dawson says “a little more than that.”)

According to a copy of a letter of demand written by Pelosi and obtained by ANIMAL, Diaz and Dawson were, “along with the late Jean Michel Basquiat, [a] graffiti and art collective under the name SAMO© that was active in New York between 1977 and 1979. During this period my clients were influential participants in the culture of New York’s East Village. SAMO© is known worldwide and my clients’ participation in the collective and contribution to it is recognized throughout the world.”

Such breathless hype raises further questions, because both Dawson and Diaz can be extremely sarcastic about the notebook. Dawson often describes it as “a fucking high-school doodle book.” And yet the two don’t pretend to be uninterested in the money it represents. Stephen Torton, Basquiat’s former assistant, who refused to comment on this story, is trying to enlist Dawson and Diaz in a plan in which they would, according to Dawson, “travel the world with the book, lecturing about it.” Of course, until a few months ago, Dawson thought the notebook was gathering dust in the back of his closet, then suddenly he’s looking at it in the elegant confines of the Beinecke, so perhaps you can’t blame him for a little confusion.

For Diaz the issues involved are even more acute because he, being essentially SAMO©’s co-creator along with Basquiat (a claim that Dawson endorses), is seeking ownership of the copyright to SAMO©, which now belongs to the Basquiat authentication committee. Interestingly, this authentication committee, headed by Jean-Michel’s father, is closing up shop this month, for reasons that remain unclear.

This development is curious, to say the least, in the light of the periodic emergence of Basquiat forgeries, which are notoriously easy to pull off because of the late painter’s exceptionally “naïve”—in art-critical parlance—style. In addition, Basquiat was incredibly prolific and was known to give his sketches, drawings and paintings to friends and even strangers on a whim, so that establishing a clear provenance, a crucial step in authenticating a “genuine” Basquiat, can be extremely difficult.

Andrew Goldstein of Artspace, one of the few aware of Diaz’s contribution to SAMO© says: “you can’t blame him for wanting to cash in. [He] deserves his due.” But he also describes the book as basically a “inside pot joke” between a few friends. But in a book filled with meta-references and druggy-wit, some passages stand out as ironic or even downright prophetic. A line in a stream of conscious riff about getting older reads “And getting over on the whole art establishment that doesn’t even really exist.” That idea became such a part of Basquiat’s legacy that Phoebe Hoban’s 1998 biography about the painter was titled: “A Quick Killing in Art.” Even so, asked about that particular page, Dawson says, “Jean didn’t write that.” If so, daydreaming about of pulling off such a hustle was not uncommon among the SAMO© group.

As for how much the spiral notebook might be worth, most of the art-world experts I consulted seemed to subscribe to a code of silence worthy of the Mafia’s omerta. But after looking at a reproduction of the notebook, scanned from the Beinecke’s archives, an appraiser at Sotheby’s, who asked to remain anonymous, estimated that the notebook might fetch at auction around $100,000 or “slightly less.” The representative added that a private collector with a strong stake in rare manuscripts would probably pay much more, meaning that in Yale, Horowitz had found the perfect buyer.

Basquiat’s career was in decline towards the end of his life. His last show, in 1988 hadn’t sold at all. He worried that his worst critics, like the then-powerful, high-modernism-worshipping Hilton Kramer, were closing in for the kill. (A typical assessment of Basquiat’s oeuvre by Kramer can be found in Tamra Davis’ recent documentary Radiant Child: “[Basquiat’s] contribution to art is so miniscule as to be nil.”) Acknowledging this strain of criticism in its review of the Hoban biography under the headline “Hyped to Death,” the New York Times wrote, “Hype made Basquiat, and hype distorted his career.”

Since his heroin-related death in ’88, however, prices for Basquiat’s paintings have soared ever upward. (Back in May, an untitled ’81 painting set a record auction price for the artist, $16.3 million.) But as the tussle over the “SAMO notebook” proves, Basquiat’s legacy is still vulnerable to criticisms, like Kramer’s, that he was “a hustler,” a master of hype. If he could have imagined the waves of controversy the SAMO notebook would create far in the future, a teenage Basquiat would probably have laughed. After all, as Diaz says, “SAMO [the graffiti collective] was a study in hype, how far we could take it.”