On February 17, 1967, the newspapers ran stories about a sensational new investigation into JFK’s assassination, headed by a New Orleans DA named Jim Garrison, who called into question the “lone gunman” theory laying all the blame on Lee Harvey Oswald. Five days after the story broke, the prime target of Garrison’s investigation, David Ferrie, a right-wing pilot linked to the CIA, was found dead of a “cerebral hemorrhage.”

Public opinion was polarized over JFK’s assassination. Forty-six percent of Americans doubted the Warren Commission’s finding that Oswald “acted alone;” Garrison was becoming more vocal about Oswald’s alleged CIA connection; and independent journalists were asking potentially embarrassing questions. Nerves in Washington were frayed.

Then on April 1, the CIA circulated an extraordinary memo instructing agents how they could play the mainstream media in order to discredit all the speculation of CIA involvement. The top-secret memo—marked PSYCH for psychological warfare—read in part: “Employ propaganda assets to [negate] and refute the attacks of the critics. Book reviews and feature articles are particularly appropriate for this purpose.”

So the CIA instructed its media assets to plant book reviews designed to debunk conspiracy theorists. And lo and behold, almost five decades after the assassination, mainstream media reviewers in the daily and weekly press are still carrying out the CIA’s orders, willingly or unwillingly. The New York Times has been especially zealous in this respect. The Village Voice ran a detailed report in 1992 on how the Times has managed the JFK assassination story; what they found is that over the years, in the rare instance of a reporter trying to file a dissenting opinion on the JFK assassination, the piece was either killed, or drastically altered. (A meticulously researched 14,000 word piece published in 1972 by Reason Magazine, “How All the News About Political Assassinations in the United States Has Not Been Fit to Print in The New York Times,” documented the august daily’s unwillingness, all the way back to the day of the assassination, to brook any alternative to Oswald’s sole guilt.)

Now, in response to a flurry of new books dealing with issues related to JFK’s November 22, 1963, assassination, the mainstream media have gone back to defending the “coincidence theory” consensus, but oddly enough they’re even more aggressive now than before —going so far as to question the sanity of people who doubt that Oswald “acted alone.”

The Times is again at the fore, using reviews of fiction, obituaries and even television coverage to smack down “lone gunman” doubters. On February 17, hipster-in- residence, Dave Itzkoff, sneered at Oliver Stone’s “opinionated — some would say imaginative — takes on notable American events and figures.” The December 7 obituary of Malcolm Perry, the surgeon who performed a tracheotomy on the dying president —a procedure that made it much more difficult to forensically identify the wound—speculated as to why Dr. Perry refused to speak to the press: “[P]erhaps because he regretted contributing, however inadvertently, to the various conspiracy theories that have sprung up despite the Warren Commission’s conclusion that Oswald acted alone,” the Times man mused. But through it all, as urged in the CIA memo, book reviews have stuck to the coincidence-theorist program.

The NY Times doesn’t only carry the CIA’s water in covering the JFK assassination aftermath. Frances Stonor Saunders’ highly respected history of the CIA’s influence on American arts and letters during the 1950s and 60s, The Cultural Cold War, singles out the Times‘ book review page being specifically prone to Agency influence. “Sometimes reviewers of books in the New York Times or other respected broadsheets were penned by CIA writers under contract,” she writes.

Those who try to question the assassination “lone-nut” consensus could find out about the Times’ unwritten editorial policy the hard way. The paper’s first edition, on December 1st 1970, carried a provocative, mostly positive, review of Jim Garrison’s book Heritage of Stone—by then newly minted critic, John Leonard. Citing a string of hard-hitting forensic questions about the assassination raised by Garrison, Leonard strongly implied that the DA might have been on the right track. He wrote: “Something stinks about the whole affair.” But immediately after it ran, the newspaper pulled it, scrubbed it, and ran an altered version of review in subsequent editions, which was much more keeping in the spirit of the consensus. Leonard was promoted to editor of the Sunday Book Review, but the incident left a sour taste in his mouth. From then on, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, a thoughtful purveyor of the Warren findings, who had panned Mark Lane’s Rush to Judgment, handled assassination books.

“The only reason I continued to review assassination books was because they fascinated me,” Lehmann-Haupt wrote me. “It did not reflect any policy of the paper whatsoever.” But he admits Times editors made their opinions known about a range of subjects in more indirect ways, which still affected coverage. In 1977, a still rebellious John Leonard filed a piece on the book My Story,by Kennedy mistress and Mafia moll Judith Exner. (She made waves in 1975 when the Church Committee investigating CIA crimes subpoenaed her.) Managing editor Abe Rosenthal–a notorious Agency suck-up– killed it.

Kennedy assassination references materialized in Lehmann-Haupt’s fiction reviews as well. The protagonist of The Magician, by Sol Stein, was portrayed as, “one of those `types,’ like Lee Harvey Oswald and James Earl Ray, who are born to lead, but lacking the equipment to do so, must assassinate the true leaders.” Coincidentally, Stein, an intellectual Cold Warrior, had served as Executive Director of the American Committee for Cultural Freedom, an Agency-backed operation, in the 1950s.

In 1993, Lehmann-Haupt championed serial-plagiarist Gerald Posner’s Case Closed–still considered the definitive defense of the Warren Commission’s version of events. Described—in one of the Times’ more tepid critiques of his work— as, having “built his literary career in no small part on debunking popular conspiracy theories,” Posner has never wanted for space in the Times. One of his pro-Establishment Op-ed page contributions was “Single Bullet, Single Gunman,” published February 2007. And it’s continued until recently: In December 2009, Bryan Burrough, writing in the Book Review, praised Posner’s latest piece of non-fiction Miami Babylon. But last month, Posner’s luck ran out. After being caught plagiarizing pieces he filed for the Daily Beast, it was quickly discovered that long passages of Miami Babylon were lifted from another Miami history, Frank Owen’s Clubland. So now it turns out that the chief propagandist promoting the Warren Commission’s theory has been outed as a liar and a fraud—or in Posner’s own words, “Yeah, I’m a thieving cocksucker.”

Burrough is positioning himself as the Times‘ next-generation debunker-cop: In 2007, he handled the review of Vincent Bugliosi’s 1,612-page Reclaiming History, a much denser and more rigorous defense of the Warren Commission than Gerald The Thieving Cocksucker could manage. But once again, Burrough’s review was so full of over-the-top praise that it verged on bad parody. Lauding the doorstop as a “public service,” Burrough stood up and saluted it: “It’s time we marginalized Kennedy conspiracy theorists the way we’ve marginalized smokers.” And then there’s the Times‘ chief critic, Michiko Kakutani, who wields considerable might in the publishing world: she too has been equally enthusiastic in hurling brickbats at lone gunman skeptics. In a February 15 review of Voodoo Histories, an epic put-down of a wide range of conspiracy theories by British neocon columnist, David Aaronivitch, Kakutani lays it all on the table. Repeating Aaronivitch’s reference to a poll that found 40% of Americans believe in “a Kennedy conspiracy,” she cracks: “It’s enough to make the characters from X-Files… Proud.”

In fact, it’s even worse than Kakutani lets on. An ABC poll taken in 2003 found that “7 in 10 Americans think the assassination of John F. Kennedy was the result of a plot.” Not to mention the 1979 the House Select Committee on Assassinations which found that there was a “probable conspiracy” to kill Kennedy; or the real-life CIA conspiracies documented in the 1975 hearings of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence–including a scheme to supply anti-Castro Cuban dissidents with a rifle equipped with a telescope and silencer. Perhaps Kakutani avoids referring to these facts because they run counter to Aaronovitch’s overarching thesis that modern conspiracies are fantasies cooked up by civilization’s discontents.

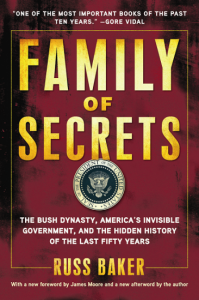

Into this vortex of institutional skepticism and editorial consensus steps Russ Baker, an investigative journalist who has been published in just about every heavyweight publication, including the New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and the New York Times. His contribution to the JFK controversy is a 500-page, a massively footnoted history of the rise of the Bush family, titled Family of Secrets. Not only does Baker challenge the conventional wisdom that Oswald “acted alone,” he argues forcefully that the JFK assassination was a successful coup pulled off by a “globally reaching, fundamentally amoral, financial-intelligence-resource apparatus.” At the center of this anti-democratic clique, which operated feverishly in Dallas around the assassination, was a 39-year-old deep-cover CIA operative named George “Poppy” Bush. Since then, with the help of its planted assets in the media, the power of the financial-military-intelligence elite has only grown. And with it, the power of the Bushes, who, like some tribe of malign Zeligs, were present at virtually every pressure point in our recent history, including Watergate.

The country’s collective image of “Poppy” Bush has been shaped by a few broad biographical strokes: genial patrician who, after flying a fighter in the Pacific and a political career of ups and downs, finally lucked his way into the presidency in 1988. (His brief stint as the CIA’s “first civilian director,” in 1977, when the agency was under fire from Congressional investigators—the Church Commission in the Senate, and the Pike Commission in the House– might be referenced in passing.) An unwitting illustration of just how pervasive is Bush’s benign if bumbling public persona came from stand-up comic– and fierce Warren Report critic– Mort Sahl in 2004. Deadpanning that Bush had once asked him who he would get to run the CIA, Sahl quipped: “Why don’t you get the guy who ran it when you were ‘running’ it?”

Yet the public record has long held clues that hint at a darker reality. Baker cites an FBI memo from November 29, 1963, in which FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover reports having briefed “Mr. George Bush of the [CIA]” after the JFK assassination. While the memo proved a mild Beltway curiosity in 1988, when the Nation first broke it, Bush was able to duck the issue by denying he was that George Bush. A different “George Bush” was identified who had worked as a clerk in the CIA—but it was found to be implausible that Hoover would have contact with someone as low-ranking as the other George Bush, and the mystery remained.

One of Family of Secrets’ most tantalizing threads centers on Bush’s long-time relationship to George de Mohrenschildt, a mysterious right-wing White Russian who was Lee Harvey Oswald’s “mentor.” Bush has long stated that he does “not recall” where he was on the day that Kennedy was killed, making him one of the only Americans who was an adult at the time not to remember that day—but his lapse of memory becomes even more strange when one considers Bush’s similar evasions on Iran-Contra.

Baker cuts through the multiple layers of noise (he would say disinformation) to establish once and for all Bush’s whereabouts on that fateful day.

The timeline of Bush’s movements are almost impossible to read without raising suspicions:

1. George Bush Sr. spent the night of November 21—and early the next day morning—in Dallas at the Sheraton Hotel. The next day, November 22, Bush flew out of Dallas on a friend’s private plane to nearby Tyler, Texas, around 12:30 PM, the time of the shooting.

2. Surfacing in Tyler around 1 PM, he begins a scheduled talk to a local Kiwanis club. After being interrupted with the tragic news, he stoically halts the speech. At 1:45 he calls the FBI in Houston to claim that a local [Dallas] GOP employee, James Parrott, was acting suspiciously and might be JFK’s shooter. Parrott turns out to be harmless and childlike.

3. Later that same day he flies back to Dallas again, but leaves immediately—on a civilian flight—to return to Houston, where he lives.

Unsurprisingly, Bush “does not recall” making the FBI call from Tyler, which Baker sees as a transparent ploy to establish an alibi. Barbara Bush has added another layer of doubt by admitting, in her vaguely sketched memoir, “Barbara Bush: A Memoir,” to spending the 22nd with the wife of Al Ulmer, a CIA “coup expert.” While Baker may be too quick to interpret these facts in the most damning possible light—that Bush was directly involved in the assassination—Bush’s actions certainly cast doubt on his claim to “not recall” where he was on that momentous day. Which raises the truly serious question of what he is trying to hide.

Baker reveals that in addition to Bush, a dazzling line-up of powerful players, who each harbored hatred of Kennedy—including Richard Nixon, who gave a speech to a beverage convention—were in Dallas on or around November 22. Allen Dulles, who had been purged by Kennedy from his CIA directorship in 1961 after the Bay of Pigs fiasco, spent time in Dallas in late October, ostensibly on a book tour promoting his tell-nothing memoir, “The Craft of Intelligence.” (Baker does not mention the fact that Dallas’s mayor, Earl Cabell, was the brother of Air Force General C.P. Cabell—the CIA’s Deputy Director under Dulles.)

While Baker admits that all of these facts could amount to nothing more than an incredible series of coincidences, at the very least his portrayal of the elite’s powerful and coordinated behind-the-scenes machinations to consolidate power – which reached critical mass at the time of Kennedy’s assassination, and culminated in George W. Bush’s stolen election in 2000 – reminded me of the Roman Republic’s transition to empire as described in Edward Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.” Indeed, Baker’s W. seems eerily reminiscent of Gibbon’s Augustus, who “at the age of nineteen [assumed] the mask of hypocrisy, which he never afterwards laid aside.” Augustus, Gibbon adds, “was sensible that mankind…would submit to slavery, provided they were assured that they still enjoyed their ancient freedoms.”

**

In the fall of 2008, as the publication date for “Family of Secrets” approached, establishment reviewers signaled growing interest. Michiko Kakutani of the New York Times asked for a reviewer’s copy. Professing enthusiasm about the book to its publisher, Bloomsbury, Time magazine’s Lev Grossman floated the possibility that Baker could make his case to Time’s readers in an online op-ed. Understandably, Baker began to feel his book might become an “an instant blockbuster.”

The first review of “Family of Secrets” appeared in Time’s December 17, 2008, issue, the same one that named Barack Obama “Man of the Year.” But the review was only 164 words long–leaving Grossman with just enough space to blurb Baker’s two most shocking assertions: “The prodigiously industrious investigative journalist Russ Baker has drawn [dozens of connections] between President No. 41 and the assassination of President No. 35,” he writes. “He also connects the dots between the Bushes and Watergate.” So there you have it: Credibly sourced claims that “Poppy” Bush was involved in two acts of high treason – charges laid down by a seasoned mainstream reporter and duly noted in the leading journal of the midcult establishment. Major media names like Bill Moyers, Dan Rather and Gore Vidal lent their praise to Baker’s book. Surely, Meet the Press and Hardball would come knocking on Baker’s door next—and the Bush family would be rocked back on its heels. Says Baker sadly, “That’s how it would have played out if the system worked,” he told me in an interview.

Baker—a Columbia j-school grad who trained Serbian journalists for the State Department in the 90s—found out very quickly that the system did not work. After it became clear that his book was being ignored by the majority of the mainstream media, Baker fell back on Plan B. By late January 2009, he had embarked on a low-rent talk-show circuit, comprised of public access TV shows and Internet radio programs. (When New World Order-obsessed phony-preacher Alex Jones asked Baker if he was afraid of being murdered, Baker replied dryly: “No, my health is just fine.”) In blurbing the book, Bill Moyers had commented: “A lot of us look to Russ to tell us what we don’t know.” Yet this magnum opus of one of America’s brightest and hardest working reporters had been pushed to the fringes of American consciousness by the collective spokes-apparatus of the Establishment. I wanted to know why.

After several attempts to penetrate the sheer volume of its reporting, “Family of Secrets” hooked me in. Baker pulls no punches in exploding the myth that the CIA performs covert operations only on foreign soil. In chapter after chapter he offers a glimpse of how power is really exercised in this country—and has been since the 1950s, when the seeds of a covert-police state were laid. While I’m not willing to swallow every connection Baker makes, there are hundreds and hundreds of well-documented and carefully footnoted facts that deserve a fair hearing. So far, they have received nothing of the sort.

In hindsight, Time’s review—printed in a comically slim sidebar found to the far right of a full-page pictorial, “History of the Times Square New Year’s Eve Ball”—was rife with clues as to what the establishment had in store for “Family of Secrets.” No one, least of all Baker, should have been surprised that Time’s editorial brass made it a point to literally marginalize—and scoff at—Baker’s work. Prescott Bush’s “close friend and fellow Bonesman,” Henry Luce, Time’s founder, makes numerous appearances in the book using the Time-Life empire to provide cover for the CIA. He put up capital for “Poppy” Bush’s first spy-fronting business, a murky off-shore oil company named Zapata; he threatened John F. Kennedy with Time’s wrath; he purchased Abraham Zapruder’s famous color film of the assassination and kept it hidden from public view for over a decade, until it was pried out and finally released, shocking the country with visual evidence strongly suggesting that one shot hit Kennedy’s head from the front. Grossman didn’t respond to my attempts to get him to explain just how his piece wound up edited down to such a tiny blurb. Time has a long-standing caste system, favoring unseen rewrite men at the top. Conspiracy-minded readers might be forgiven for wondering if Grossman, known as something of a stylist, would voluntarily mar his prose with a made-up adjective, “farfetchedly,” especially when it seems to undercut his thesis.

But the sleaziest attempts to undercut Baker’s book came from the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post—the papers notorious for their campaign to discredit and destroy Pulitzer Prize journalist Gary Webb–the heroic San Jose Mercury reporter who exposed the CIA’s connection to the ghetto crack epidemic in 1996. Their campaign worked—Webb was eventually demoted and finally committed suicide. With Baker’s book, the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post went back to work discrediting their colleagues who dare to get out of line. Tim Rutten, a bearded LA Times metro-desk tool, filed his handiwork on January 7, 2009. After framing his attack by quoting long passages of Richard Hofstadter’s 1964 book The Paranoid Style in American Politics, Rutten goes after Baker with bizarre language that reads like some fanatical Bolshevik. He decries the very existence of Family of Secrets as a “reprehensible calumny” and denounces Baker’s reliance on “mind-numbing accretion of names, dates and places”– in other words, too many facts. That any American would even question the findings of the Warren Commission makes Rutten sputter with rage: “I regard the belief that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone as an important indicium of mental health,” he writes. Two months earlier, Rutten had been the proud recipient of the Anti-Defamation League’s Hubert H. Humphrey First Amendment Freedoms Prize. The last time I looked, the First Amendment was about encouraging freedom of speech, not vilifying the bearer of unpopular opinions

“Rutten actually did me a favor.” Baker says, a rare smile passing over his face. “It was so over the top that people in LA started to pay attention.”

Writing in the January 11 issue of the Washington Post, former Spy-editor Jamie Malanowski refused to even consider the possibility that the elder Bush would lie to protect his cover; that is, to deny he was a part of the CIA until 1977, when he became the agency’s first “civilian” director. Citing a 1988 denial by “a spokesman for the then-vice president,” Malanowski dismisses the memo from J. Edgar Hoover linking “Mr. George Bush [CIA]” to a November 29, 1963, briefing on the assassination. (Oddly, the Post’s hawk-eyed proofreaders nodded when Malanowski referred to Baker as “Smith.” Former Slate media-critic Russ Smith is a nearly universally despised figure in journalism.)

It’s hardly surprising that the Post review fails to disclose Baker’s damaging exposes on the Washington Post’s well-documented links to intelligence and domestic propaganda. “Family of Secrets” offers a trove of evidence that calls into question Bob Woodward’s—and by extension his editor Ben Bradlee’s and the Post’s—trustworthiness. The Watergate myth (enshrined by Hollywood in the movie “All the President’s Men”) tells the underdog story about how a plucky pair named Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein cracked Nixon’s complicity in the break-in, and how the two reporters managed to do it all with only shoe-leather and a conveniently voluble insider-informant (or in fiction terms, a “cheap literary device”) known as “Deep Throat.” But Baker raises evidence that Woodward, who served five years in Naval Intelligence in the 1960s, as a long-time deep-cover intelligence operative advancing his handlers’ hidden agendas. Of course, the Post will argue that any reporter who says that Naval Intelligence counted Ben Bradlee in its ranks during WWII, and that Paul Ignatius, the Post’s president until 1971, was secretary of the Navy under Lyndon Johnson, suggests an addiction to “mind-numbing” facts that raises questions about the author’s mental health. Better to de-numb the mind with fewer facts.

Demonstrating just how convoluted the real-world machinations of the intelligence community can be, Baker has dug up an undated memo from Charles Colson, then Nixon’s Special Counsel, that reads, in part: “The CIA has been unable to determine whether Bob Woodward was employed by the CIA.” This extraordinary document goes on to say that the CIA director had gotten the message to Woodward—who was reportedly “incensed” that his murky connections were being looked into.

No one today doubts that George W. Bush transformed the country for the worse, in ways that won’t be fully understood for decades. By the time W. and his cabinet hunkered down in the White House for their final days, however, elements of his legacy had emerged: a politicized Supreme Court ever willing to curtail civil liberties and protect corporate interests; a never-ending war at home and abroad against a sketchily defined, shape-shifting supranational enemy; a highly concentrated and virtually unregulated banking elite, which in the process of amassing unheard-of fortunes left a great recession in its wake. (Even Bob Woodward, who earlier in W.’s first term penned an admiring volume about Bush 43’s administration, had become highly critical by the end of his second term.) The disaster we’re now in deserves more investigations with more open minds—the very opposite of what the establishment will allow. Back in December 2008 the besieged mainstream media—busied with breathless blanket coverage of Barack Obama—was in no position to even raise the key question, namely: How did this dyslexic princeling, son of a one-term president, steal an election, start two endless wars, wreck the financial system—and get away with it?

Seemingly alone among American journalists, Baker had the guts – and smarts – to at least try to answer this question without falling into the mainstream trap of self-censorship. Explaining to me how he wound up getting pushed out into mainstream Siberia, he says: “You can’t even ask if the conventional surface explanation is adequate, let alone totally wrong.”

I’m sitting with Baker in an upscale East Village café, listening to him argue his case. Middle-aged, with preternaturally youthful features, hooded eyes, and short graying hair, he wears the uniform of a typical middle-aged professional: glasses, white designer tee shirt and leather jacket. His voice barely rising above a whisper, he says: “I’m as shocked at the stuff in my book as my readers.”

“Poppy” Bush has long been on his radar.

On September 21, 1991, Baker published a scathing feature in the Village Voice, entitled “CIA: Out of Control.” Baker’s article argued that the Agency was scrambling to find new “bogeymen to vanquish” after the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, and amid this scramble for a new enemy, Baker wrote, “Bush has worked unceasingly to weaken the checks and balances that were instituted following a string of White House-connected scandals in the 1970s.”

Baker himself is a man without definable qualities, except for hints of an East Coast formality inconsistent with the vibe of the town where he grew up: Venice Beach, California. You can easily come away from a long conversation with him wondering who he really is. He even refuses to give his age. Adding to his sense of mystery, when pressed, he sketches out a hazy background, which includes: time spent working in a “family importing business;” “a father who was an officer in the Air Force and worked in the aerospace industry, simultaneously;” “a mother originally from Europe.” Whatever the genesis of Baker’s disgust with the Bushes, few would deny that in the years following his Voice article, the trend towards weakening checks and balances—and towards manufacturing new bogeymen—went haywire.

“You can be a reasonably good political reporter without ever coming across this stuff about Bush,” he says, charitably. But despite his dry demeanor, it is clear that his treatment at the hands of the mainstream media, especially the Times, stings him deeply, and his mood begins to visibly sink when the subject of his freeze-out is raised.

Asked why the Times gives so much space to conspiracy de-bunkers like Posner while ignoring Family of Secrets, Baker says: “It’s a mind set.”

He attributes the inability of his nominally liberal peers to even consider his findings to “cognitive dissonance.” In other words, it’s just too jarring for the average Manhattan liberal, who Baker says is primarily interested in “yoga, food and feng shui.” Journalists especially are almost by nature part of and ingratiating themselves into the Establishment, he explains. “When you’re in the status quo, you’re invited to a lot of dinner parties. Even if you watch Jon Stewart, you can still think things are OK,” he says. “If you have to stop and say ‘Oh my God, something scary,’ you can’t function”

“Journalism is not a moral business,” he says finally.

But it is supposed to take its role as one of the checks and balances seriously, if this country is going to function properly.

On December 22, 1963, a month after JFK’s assassination, the Washington Post published a confounding editorial by ex-President Harry Truman in which he attacked the power of the CIA. Truman was a beloved figure across the country—and yet even he couldn’t defeat the Washington Post’s censors. Incredibly, former President Truman’s piece was quickly yanked from subsequent editions of the Washington Post, as if it hadn’t ever been published. But the record of it remains, and it is worth re-reading Truman’s ominous final sentence, published one month after JFK’s murder, which reads: “There is something about the way the CIA has been functioning that is casting a shadow over our historic position and I feel that we need to correct it.”

According to Baker, that need has only grown more pressing