Animal

May 16, 2012

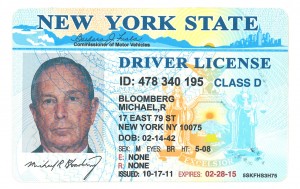

Is this Mike Bloomberg’s real driver license?

Worried over reports of a spike in sales of fake IDs in Jackson Heights, Queens, State Sen. Jose Peralta, (D) has proposed stiffer penalties for perps accused of being part of what he deemed a thriving racket more lucrative than drugs. That last phrase made headlines back in February, when a street-smart New York Post reporter was able to score a veritable new identity (passport, license and social security card) for the bargain-basement price of $260 along Roosevelt Ave. While Sen. Peralta’s concern may be understandable, the truth about the underground fake ID market is that it is fed by forces operating far outside of the New York legislature’s jurisdiction. Mostly.

There are local players eking out a living selling high-end fake ID’s in Jackson Heights and elsewhere. And for casual purchasers–the young drinkers–the major suppliers are offshore websites, especially ID Chief, which is widely believed to be based in China. Even when the fakes are assembled locally the forgers usually rely on materials ordered from overseas sites, which operate–like ID Chief–in a sort of legal twilight. Every year ID Chief and similar websites pop up in college or even high school newspapers when a big-man-on-campus type gets busted after his bulk order–a method that is encouraged by the sites’ graduated pricing system–is stopped at U.S. customs.

A big man in the local fake ID racket is forty-seven-year-old Chris Green [not his real name], a mile-a-minute talker with a short fuse and a nasty case of fibromyalgia that periodically fells him with sudden, excruciating pain. His muscular frame belies the fact that he works mainly from bed. But his astonishingly varied resume–which includes (but is not limited to) diplomas from two highly competitive northeastern universities, a gig with the federal government, a Japanese prison bit, a stint as a famous House DJ and ownership of a notorious record company–makes him a first rate source on the city’s still-fertile, if somewhat muted underground economy in the waning years of the Bloomberg era. If the streets are awash in something illicit–from bootleg cigarettes and fake Vespas to pills and powders–he’ll be part of the action somehow.

So it’s no surprise that Green has a hand in the latest illegal activity to blow up in the tabloids, and he can only hope that it pays better than illicit drugs. Pills–from the harder core like Oxycontin and Dilaudid to the milder Valium and anti-depressants–have long been his bread and butter. Right now it’s difficult to see how his ID thing, which required a substantial outlay of capital for printing equipment, can compete with drugs on a strictly margin basis, mainly because of the sheer amount of pills he moves a month. Half of his inventory of pills is prescribed for a host of ailments ranging from fibromyalgia to “stomach cancer” by a rotating crew of doctors, and obtained virtually free through Medicare. The remainder is picked up at rock-bottom prices from residents of the Avenue D projects and flipped to his better-heeled clientele. He isn’t exactly getting rich, but on a good month he’ll make “thousands, easy.”

But just on a strictly per transaction basis there’s no denying that the profit margin is higher in fake ID’s than prescription drugs. He charges from $200 to $300 a pop for drivers’ licenses from states including New York, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Hawaii. Most of his customers want a NYS license; there’s no problem finding prospective customers in the nearby bodegas and projects. In a couple months time by word of mouth alone he has already produced dozens of licenses for as many customers and currently has 20 orders for more, including a request for a fake birth certificate. (Commissions for Michael Bloomberg IDs, like the one Green made [shown above], are uncommon.)

Hugh O’Rourke, a former NYPD detective and current counter-terrorism expert with a private security firm, admits that with “a lot of money and a lot of time” it’s possible to secure a new identity on the street. But he remains sanguine that even the finest forgeries by operators like Green will “have some flaw somewhere.” The key document, he says, is a birth certificate, which, done right, can be “very valuable” because it serves as a springboard to get the other papers a perp needs to go on the lam as someone else.

As with all his other forging needs, the key document Green would need to create a passable birth certificate–namely, the seal from a given bureau of vital statistics–is readily available from purveyors on the Chinese website Alibaba.com. Ticking through the process of how he could get someone in China to create a seal for his “original artwork,” Green gives a short laugh and says, “You think the Chinese government cares about this shit?” Asked if his fakes, which cost three times as much as those available on ID Chief, are worth the premium, Green insists, “Mine are much, much better.” He notes that ID Chief seems to be admitting as much when the FAQ sheet on their site reads: “all ids are good except pa [Pennsylvania] is better [sic].”

Green has invested so heavily in his fake ID venture that his bedroom looks like a Kinko’s supply closet. There are multiple high-end printers–2 Epson 280s and 2 Artisan 50s, an oversized Epson–along with magnetic strip encoding hardware, dry erase boards, die cutters, an industrial laminating machine, a paper-cutting tray and the inevitable array of locked file cabinets. Not to mention two of his recent additions: a black light lamp so he can catch any imperfections the way a government agent might, and an RFID chip encoder, which enables him (at least, theoretically) to duplicate the hologram-enhanced NYS license (which so troubled civil libertarians when it was introduced in 2006) among other pieces of high-tech identification. Since he can’t recreate the actual holograms on his Epson, he has to buy them from Alibaba.com for a few bucks a pop. Pointing to a rack with two dozen plastic pockets each holding a different grade and size of hard plastic corresponding to different state licenses, he explains: “I call this my ‘central library.’ I made it from scratch.”

Lately he’s been spending hours in front of a large computer monitor, practicing with the templates he needs to branch out from fake IDs to forging other types of documents, including credit cards and birth certificates. Talking about the Photoshop skills it takes, he explains that some of the necessary templates are readily downloaded off the web but others are “really fucking intricate with details in layers and different layers in the details.” He is currently experimenting with the RFID encoder in an attempt to master the technology involved. “I’ll do anything to make money,” Green says, before pausing to share his post-9/11 sensibilities, “except sell a document to an Arab.”

Its obvious that these forgeries, which count as a Class E felony if he has the misfortune to get busted (according to O’Rourke, a “pretty serious” offense) affords Green with a pride of craftsmanship not found in slinging Oxycontin. Green’s customers even receive their documents in glassine sleeve stamped with his “company’s” logo, Sianotik ID. If “God forbid,” he gets busted, Green hopes that like a latter-day Frank Abignale the authorities will deem his work “so fucking good” that they’ll put him to work for them.

If Green’s clients tend to be illegals seeking some sort of official validation, or cons hoping to one day elude the law, ID Chief’s customers are mainly white-bread collegiates who want to drink in public. The new technology has already led to a noticeable lowering of the age of patrons you might find in a typical Long Island Bennigan’s on a Friday night. Bill, a 20-year-old Manhattan College sophomore, says he’s the only one of his friends who hasn’t used the services of ID Chief; so far, he’s been dissuaded by an “antiquarian” fear of giving his mailing address to a vaguely illegal multi-national.

“Other than that, I can’t really see the risk,” he says, dismissing the fact that along with a mailing address the process requires a digital picture of oneself. ID Chief has made payment relatively hassle free, requesting that purchasers use what college kids call “money grab” cards or pre-paid gift cards that look like credit cards, or for larger orders, Western Union.

Bill, who has had several fake ID’s taken away from him in his short drinking career, is contemplating five long months with a “totally shitty” fake until his 21st birthday. Meanwhile, he can’t quite suppress his annoyance that even his brother and his brothers’ friends–juniors in high school–already have fake IDs. He says: “This is the youngest crop of drinkers I’ve ever seen.”

In his efforts to avoid the ID Chief colossus, Bill was directed towards City Underground, a headshop on Sullivan Street. Perhaps owing to the heat from the recent New York Post spread, City Underground was closed. The headshops nearby claimed they had stopped their “novelty ID” business sometime ago. But persistent inquiry led Bill to a combination head shop/t-shirt emporium on Saint Marks Place called Little Tokyo where anyone can plunk down $75 for a “novelty state ID” that makes ID Chief’s wares look the finest forgery in Jason Bourne’s wallet. “We don’t make the ones that say New York or New Jersey,” an aging punk type chimed in apologetically.